The Ultimate Guide to Context Engineering for AI Agents in 2026

The long-sought potential of autonomous AI agents has been hampered by Large Language Model (LLM) limitations, notably the finite “context window”—the model’s working memory. A persistent issue, even with large windows, is the “lost in the middle” phenomenon, where LLMs forget details in the middle of a context, recalling only the beginning and end.

However, a new approach—context engineering—is emerging. This discipline focuses on intelligently managing and optimizing the information fed to an LLM, moving beyond simple prompt engineering. By embracing this holistic context management, AI agents can transition from unreliable novelties to powerful, effective tools.

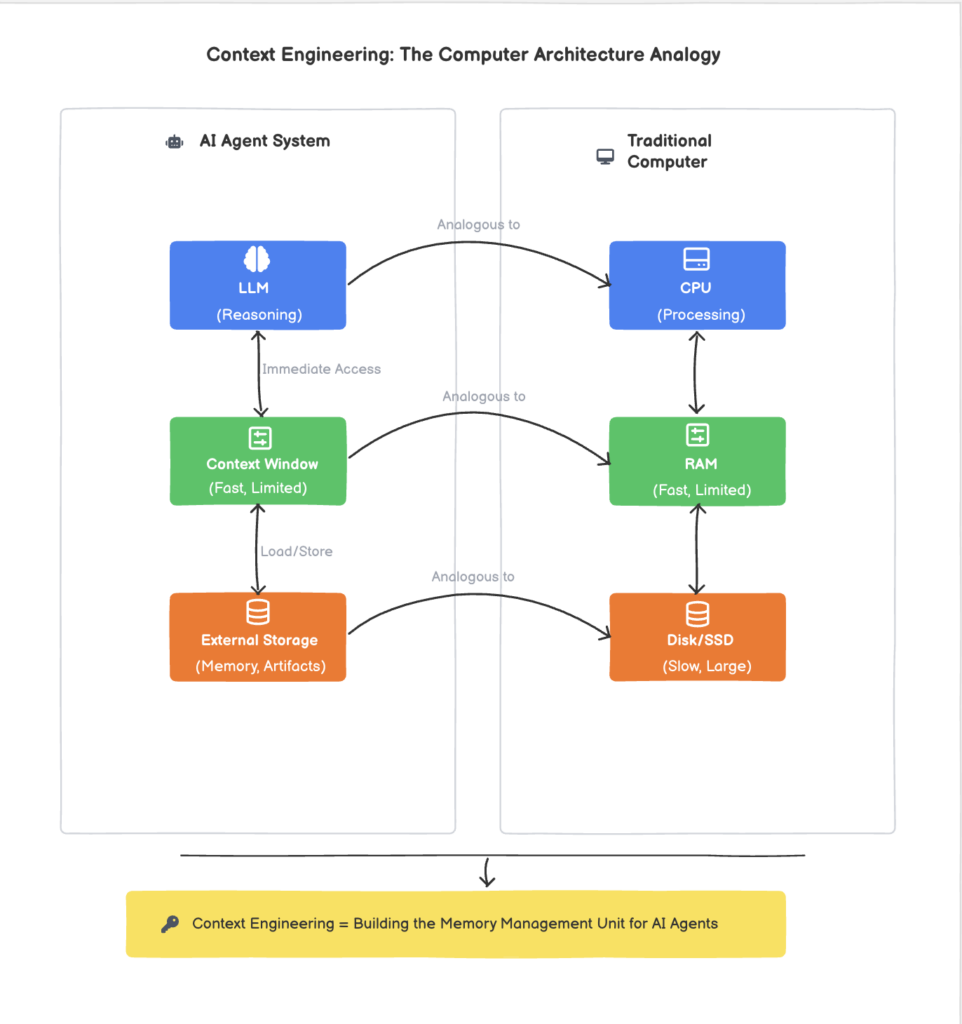

What is Context Engineering? The CPU and RAM of AI Agents

Context engineering is like managing an LLM’s context window, which acts as the system’s volatile and limited RAM. Similar to RAM limits, the LLM cannot hold all data, and the “lost in the middle” issue is comparable to inefficiently organized, cluttered RAM degrading performance.

Context engineering, then, is the art and science of building the equivalent of an operating system’s memory management unit for an LLM. It involves creating systems and strategies to intelligently swap information in and out of the context window (RAM) from a larger, more persistent storage, which we can think of as the hard drive or solid-state drive (SSD). This external storage can hold vast amounts of information, such as the entire chat history, tool outputs, user profiles, and task lists. The goal of context engineering is to ensure that the most relevant and high-signal information is always present in the LLM’s “RAM” at the precise moment it’s needed.

The Anatomy of AI Agent’s Context

Understanding different components of this context is crucial for effective engineering. Here’s a breakdown of the key types of information that an agent might need to access:

| Context Component | Description |

| Prompt Instructions | The core directives given to the agent, including both the user’s initial request and the system-level instructions that define the agent’s persona, capabilities, and constraints. |

| Chat History | The ongoing dialogue between the user and the AI Agent, providing a record of the conversation and the evolution of the task. |

| Tool Responses | The outputs from any tools the AI Agent has used, such as search results, code execution outputs, or API responses. |

| User Attributes (Core Memory) | Persistent information about the user, such as their preferences, goals, or background, which can be used to personalize the Agent’s responses. |

| Task List (for Thinking Systems) | A structured list of tasks or sub-goals that the agent is working on, which is particularly important for complex, multi-step problems that require a “thinking” process. |

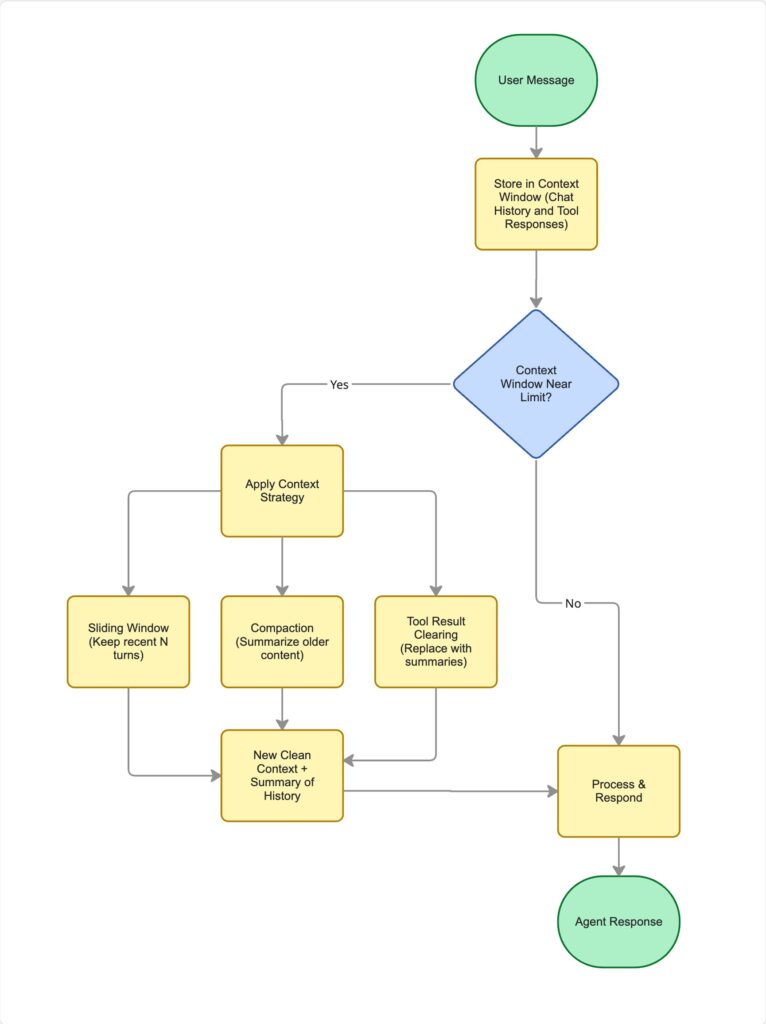

Contextual Engineering for Short-Term Tasks: The “Non-Thinking” Agent

For many common agentic tasks, such as customer support automation or simple information retrieval, a deep “thinking” process is not required. These agents are designed to respond quickly and efficiently to user requests, and their context management strategies reflect this need for speed. In these scenarios, the primary goal is to maintain a coherent conversation while avoiding the pitfalls of an overflowing context window.

The main strategy for this is compaction, the process of taking a conversation that is nearing the context window limit and distilling its contents in a high-fidelity manner. The art of compaction lies in the careful selection of what to keep and what to discard. There are several ways to implement compaction:

1. Sliding Window with Summarization

This is a common compaction technique. As the conversation grows, the oldest turns (the “window” slides forward) are removed from the context and replaced with a summary. This retains the gist of the early conversation while freeing up space.

Conversational Use Case: A customer support chatbot is helping a user troubleshoot a complex issue with their internet service. The conversation has been going on for over 20 turns, and the context window is nearly full.

User: “It’s still not working. I’ve already tried restarting the router and checking the cables like you said.”

Agent (Internal thought): Context is getting long. I’ll apply a sliding window with summarization. I’ll summarize the first 10 turns to make space while preserving key information.

Agent (Internal action): [Compaction: Summarize turns 1-10: User reported slow internet, confirmed router model, and restarted it.]

Agent: “Okay, thanks for confirming. Just to recap, you’re experiencing slow speeds, and you’ve already restarted the router. Let’s try a different approach. Can you please run a speed test at…”

2. Selective Compaction

This is a more advanced technique where the agent doesn’t just summarize the oldest parts of the conversation, but selectively extracts the most relevant information from the entire context stored externally based on the current turn of the conversation.

3. Tool Result Clearing

This involves replacing the full, verbose output of a tool with a much shorter, human-readable summary once the information has been used. This summary is often written to a scratchpad, which is a short-term memory space outside the main context window where an agent can take notes. This keeps the working context clean while ensuring important details are not lost. The agent can then retrieve this information later, bringing the relevant notes back into the context window only when necessary. There are two common mechanisms for this retrieval:

- Automatic Injection: In simpler implementations, the entire content of the scratchpad is automatically added to the system prompt at the beginning of every conversational turn. This ensures the information is always available but can be inefficient as the scratchpad grows.

- On-Demand Retrieval (Tool-Based): In more sophisticated agents, the agent is given a tool to explicitly read from the scratchpad. The agent must first recognize that it needs information not present in its immediate context, and then decide to call the read_scratchpad tool. This is far more efficient and a better demonstration of true reasoning.

Conversational Use Case: A travel booking agent is helping a user find the best flight to New York.

Agent: “I found several flights to New York for you. [Displays a long list of 50 flights]. Do any of these work for you?”

User: “Great, I’ll take the United flight, UA456.”

Agent (Internal thought): The user has made a selection. I will clear the verbose flight search results from my working context to save space and write it to my scratchpad. I’ll retain the selection in my memmory and also, write the summary of the user selection to my scratchpad.

Agent (Internal action): [Clear tool result. Write to scratchpad.md: User selected flight UA456 from SFO to JFK on Dec 25th.]

Agent: “Excellent choice. I’ve confirmed your selection of flight UA456. Shall we proceed with booking your seat and discussing hotel options?”(Later in the conversation…)

User: “Actually, before we book the hotel, can you check if there is any delta flight?”

Agent (Internal thought): The user is asking for information I previously cleared from my working context. I need to retrieve it. I will use my read_scratchpad tool to get the flight details.

Agent (Internal action): read_scratchpad()

Agent: “Of course. yes, there are two flights from delta airlines.”

Contextual Engineering for Long-Term, “Thinking” Tasks

For complex, long-horizon tasks, such as writing a detailed research report or developing a piece of software, a simple question-and-answer loop is not sufficient. These tasks require the agent to “think” – to break down a complex problem into smaller, manageable steps, to reason about the best course of action, and to adapt its plan as new information becomes available. This is where the concept of “thinking” in LLMs comes into play.

What is “Thinking” in LLMs?

Recent LLM advancements introduce “reasoning tokens” or “thinking tokens,” which enable the model to perform an internal chain of thought for more coherent, well-reasoned responses. This “thinking” is vital for long-horizon tasks, but it consumes context window space.

The choice between a “thinking” and “non-thinking” agent depends on task complexity. Non-thinking agents suffice for simple, cost-effective tasks. Thinking agents are better for complex, long-horizon tasks involving:

- Long, evolving conversations

- Complex, multi-step planning and coordination

- Iterative development with plan adaptation

Architectural Patterns for Long-Term Tasks

To effectively manage context in long-term, thinking tasks, we need to move beyond simple compaction and embrace more structured and hierarchical approaches.

1. MemGPT-Style Architectures: Virtual Context Management

The MemGPT paper, “Towards LLMs as Operating Systems,” introduces the concept of “virtual context management,” which is inspired by the virtual memory systems in modern operating systems.

This approach provides the illusion of a much larger context window by intelligently paging information between the LLM’s limited context window (RAM) and a much larger external storage (hard drive).

The MemGPT architecture consists of a three-tiered memory hierarchy:

- Working Context: This is the LLM’s active context window, equivalent to RAM. It contains the system instructions, the current user message, and a selection of the most relevant information from the other memory tiers.

- Recall Storage: This is a larger, persistent storage that holds the entire conversation history. It’s analogous to a computer’s swap space.

- Archival Storage: This is a long-term, searchable storage for facts, user preferences, and other important information. It’s the equivalent of a hard drive or SSD.

- Scratchpad: External memory to writedown tasks list and other session memory details (Structured note taking explained below in detail).

The LLM itself acts as the memory controller, using a set of specialized tools to move information between these different memory tiers. This allows the agent to maintain a vast amount of information over a long period of time, while only keeping the most relevant details in its immediate working context.

1.1 Structured Note-Taking: Agentic Memory

An approach on how to write to scratchpad. In this approach, the agent is trained to regularly write down its thoughts, plans, and key findings in a structured format, which are then persisted to an external memory. This allows the agent to build up its understanding of a problem layer by layer, while only keeping the most immediately relevant information in its working memory.

This approach is particularly well-suited for iterative development tasks with clear milestones. For example, a software development agent might use structured note-taking to keep track of the project’s requirements, the current state of the codebase, and its plan for the next development sprint.

2. Multi-Agent Architectures: Divide and Conquer

Another way to overcome context limitations is to use a multi-agent architecture, where a complex task is broken down and distributed among a team of specialized sub-agents. Each sub-agent has its own clean context window and is responsible for a specific part of the task. This approach is highlighted in both the Anthropic and Google Developers blogs.

These systems treat context not as a mutable string buffer, but as a compiled output of a series of explicit transformations. Agent or Agents handoff will be a scoped memory that is needed only for that sub-agent. This allows for a much more granular and observable approach to context management.

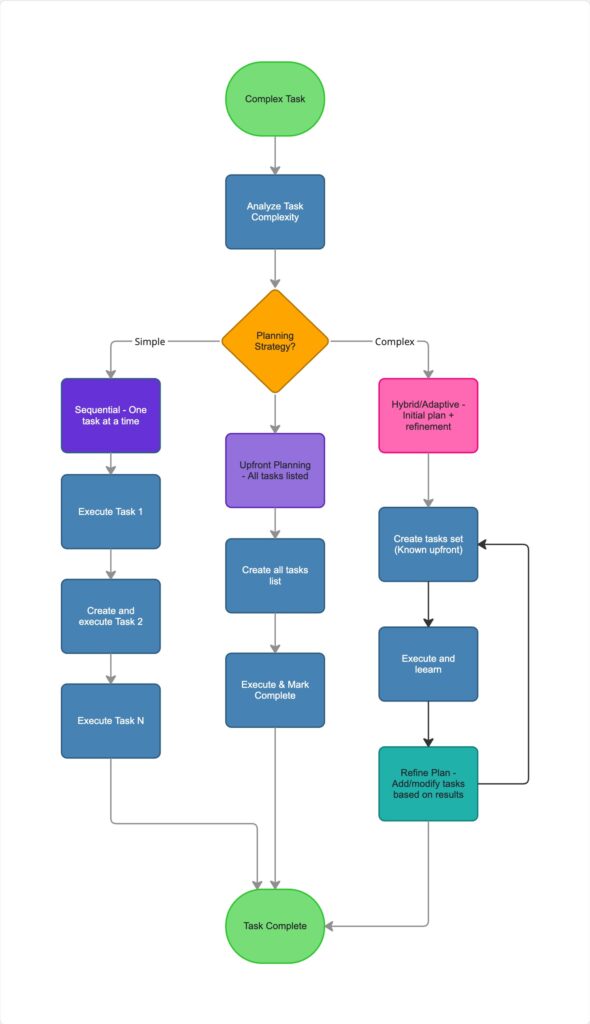

Task Planning Strategies for Thinking Agents

For thinking agents working on complex tasks, the way the task list is managed is just as important as the memory architecture. This is often where the agent’s ability to reason and adapt is truly tested. There are three main approaches to how an agent can tackle a plan, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

1. The Standard: Iterative (“ReAct” Loop)

This approach can be summarized as “Figure it out as you go.” In this default mode, the agent does not generate a full checklist of steps at the start. It only calculates the immediate next step based on the observation from its previous action. This is the core logic behind the popular ReAct (Reason + Act) framework.

Why use this? This method is highly dynamic and robust to errors. If the hotel search had failed, the agent wouldn’t have wasted time and tokens planning the restaurant booking. It can react to unexpected outcomes and navigate uncertain environments effectively.

The Risk: The agent can lose track of the original, higher-level goal (“What was I doing again?”) if the conversation gets too long or if it gets sidetracked by a series of unexpected errors. This is a classic symptom of context window saturation, where the initial user request gets pushed out of memory.

2. The Planned: Upfront Planning (“Plan-and-Solve”)

This approach follows the mantra: “Make a list, then do it.” Here, you explicitly prompt the agent to generate a complete, numbered plan before it touches any tools. The agent then executes this static plan step-by-step.

How it works:

User: “Research the history of generative AI and write a summary.”

Agent (Planning Step): “Okay, here is my plan:

- Search for the early history of AI (1950-1990).

- Search for the modern history of generative models (2010-2024).

- Combine the notes from both searches.

- Write a concise summary based on the combined notes.”

Agent (Execution): “Now starting Step 1: Searching for early AI history…”

How it is managed: This is often implemented by adding a system instruction like, “First, think step-by-step and create a complete plan to address the user’s request. Then, execute the steps in order.” In frameworks like LangGraph, this can be managed by having a plan variable in the agent’s state, which is populated by the first LLM call and then consumed by subsequent execution steps.

Why use this? It keeps the agent focused and prevents it from going down unproductive “rabbit holes.” The agent has a clear map to follow, which is very effective for tasks with a well-defined scope.

3. The Hybrid: “Plan-Execute-Replanning” (Best Practice)

This is the most sophisticated approach and is how advanced autonomous agents (like Auto-GPT or the system described in this blog) operate to get the best of both worlds. The agent creates an initial plan, but critically, it re-evaluates and refines that plan after each step.

Conclusion

The myth that “agents don’t work” is a product of our early, naive attempts to build them. By simply throwing more tokens at the problem, we have been fighting a losing battle against the inherent limitations of the LLM architecture. The future of AI agents lies not in bigger context windows, but in smarter context engineering.

By embracing a more sophisticated and architectural approach to context management, we can build agents that are capable of tackling complex, long-horizon tasks with focus and precision. Whether it’s through MemGPT-style virtual context management, or multi-agent architectures, the key is to treat context as a precious resource and to manage it with the same care and rigor that we apply to any other aspect of software engineering. When we do that, we will find that agents don’t just work – they work wonders.

“Find the smallest set of high-signal tokens that maximize the likelihood of your desired outcome.” — Anthropic

Comments

Leave a Comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!